Meditations on Death

“Death is perhaps the single greatest teacher when it comes to how large the little things in life are.” - Judy Lief

Welcome to Meditations—a space dedicated to nurture connection. Each edition will feature a meaningful exploration into a theme, blending engaging narratives and mixed media recommendations to invite deeper connections with the world around us.

My hope is that through these explorations, you will:

Discover fresh ideas and perspectives

Engage with themes that resonate, and

Find something fun and meaningful to look forward to in your inbox :)

We often celebrate the beauty of new beginnings–the start of a new year or a fresh chapter. But there’s also beauty to be found in endings. The closing of chapters carries with it its own form of meaning and grace.

In many cultures, death is seen as a transition, part of life’s natural cycle, connecting us to something greater. Yet, in Western society, we often fear death, clinging to the illusion of linear progress instead. As we find ourselves in the heart of winter, this time of year invites reflection on what has passed and what has been lost. In this space, we are reminded that even in the pain of endings, there is space for growth and renewal.

This understanding is something both PRATHIGNA and I have come to grasp in our own ways. Through our personal reflections, we explore what death means to us and the lessons it has taught us.

“Death is perhaps the single greatest teacher when it comes to how large the little things in life are.” - Judy Lief

In the darkness we grow

-Amrita

Last fall, I received a voice message from a friend. Her words, honest and thoughtful, carried the weight of an ending. I sat at the edge of my bed staring at my phone, and replayed her message, trying to absorb what it meant.

I found myself suspended in the liminal space between grief and acceptance. There was no clear moment when I understood this friendship had come to an end, but as the absence settled with each day that passed, I knew it had arrived.

Friendships, unlike other relationships, often dissolve without formal closures. There are no defined scripts or rituals to follow when they fray—just silence. In the days after receiving the voice message, I replayed old conversations and interactions in my mind, searching for signs, wondering when she must have decided to end the friendship we shared. I wished for a chance to meet and talk face to face, to better understand her truth, and for me to speak mine.

This is the part of losing a connection that no one tells you about. I wasn’t just mourning the loss of a platonic partner but also the loss of the person I was when we were close. The version of myself that no longer felt accessible.

The end of this friendship felt like a form of death—an invisible one. Not a finality, but the closing of a chapter that, in time, would make space for something new to grow. Death, in all its forms, can be viewed as the start of transformation, or rebirth. Perdita Finn, in Green Dreamer’s podcast episode, “Sitting with the Wisdoms of Darkness, Death, and Decay” says, “Everything grows in the dark. Babies gestate in their mother’s wombs in the dark. Seeds grow in the dark of the earth. We can only see the stars in the dark of the night.”

This idea of growth in darkness resonated with me as I sat with the absence. As the weeks passed with no contact, it became clear that she wasn’t interested in rekindling our connection. There was something unspoken in her absence, a kind of space, while initially perplexing, seemed necessary for both of us. I began to understand that her need for space wasn’t a rejection, but rather an invitation for both of us to grow separately. In the quiet, I found room for my own reflection of parts of myself I wanted to shed. And in that process, I found clarity.

In the end, perhaps every relationship we experience is a reflection of time—of who we were and who we’re becoming. And like time, they are fleeting, stretching across our lives in ways we can neither predict nor control. Some friendships last forever and others fade quietly. But even in their endings, they leave behind traces of love, beauty, and lessons we can carry forward.

The voice message remains on my phone alongside photos of us, digital artifacts of what once was. I’ve resisted deleting them, not out of hope or to pretend like they never existed but as a reminder of the love and joy we shared. Healing, I’ve learned, doesn’t require forgetting but moving on asks us to hold memory and grief in the same hand, to make peace with what no longer exists, and to embrace the growth that will follow.

The symbols we keep

- Prathigna

This winter, I started listening to The National again. I wasn’t sure why I was in the sudden mood for indie rock, but a part of me wanted to drift back to when the seventh-grade version of me was discovering carefully for the first time. I was too young and dramatic ever to understand their songs like Terrible Love or Lemonworld, but I sure did try. At the time, all I could hear were the equally dispiriting yet hopeful voices of Matt Berninger and Aaron Dessner, stitching together lines and phrases that read like poetic diary entries.

On a questionably warm December afternoon, something here and now prompted me to find meaning behind their lyrics. Eventually, after losing parts of my focus while feverishly digging through Reddit threads and online articles in several dozen tabs, I found an interview from 2010, tucked away in The Quietus.

In the middle of the interview, Laura Snapes initiates a discussion about water. She says, “There seems to be a lot of lyrics about escaping the city on High Violet, and escaping to water especially.”

Matt Berninger responds with:

“Yeah, that’s weird. There are things that always come back to me, like water. But then actually, I think to writing and art and poetry, everybody uses water for a million different reasons. I think I’ve probably used every type of water: a glass of water, a lake, a river, rain… There’s a song that didn’t make it onto the record that’s got wells in it too. Swimming pools all over the place, oceans… So I don’t know why! If you asked me what does water symbolize, a psychologist would tell you that it means rebirth, death or peace, all these different things…”

I wasn’t particularly drawn to the rest of the interview after this part. Instead, I found myself fixating on the things that always seem to come back to me.

Like water for Matt, symbols of death for me.

Meghan O'Rourke wrote in her memoir about losing her mother: 'The people we most love do become a physical part of us, ingrained in our synapses, in the pathways where memories are created.' I came across that in The Marginalian, while searching for other writers' and poets’ takes on death, loss, and grief. Just a casual Tuesday at the Red Bank Public Library—looking for answers to life’s most persistent questions.

It feels almost superstitious, the way I’m researching—looking for death to write this piece. But throughout my life, death has always approached me first—inching closer and closer, growing too familiar, too personal, even though I never asked for it. It’s such a deceptive thing: all-encompassing in one moment, and then life resumes, leaving behind sporadic moments of grief, often intertwined with physical objects that then become its symbols.

Sydney Sheldon’s Master of the Game became a symbol of death first, my favorite book second (yes, out of all of them). It was just some story my cousin talked about when my family came to visit India one summer. I was maybe ten—I’m not sure. I was too young to really get it, judging from its sultry cover of a woman draped in a provocative red dress. But my cousin didn’t care. Maybe it was reckless of her, but she described the plot—a tangled world of intergenerational wealth, diamond trade, sex, family trauma, and, of course, greed—like she was chatting with a friend instead of a kid.

Everyone in my family knew I was obsessed with her, the pesky younger sibling in a big Indian family. She held so many roles: a sister, a friend, a cousin, a woman I wanted to embody. Naturally, everything she was obsessed with, I was obsessed with, too.

She died when she was 27. At the time, she had left India and was living and working in Delaware, starting a new life there. I was 17, sitting in a drive-through at White Castle with my family in New Jersey when I found out about the car crash somewhere in Accomack County, Virginia. She was airlifted to a hospital in Maryland. What’s strange about that moment is that it was a time when my family and I were happy—genuinely, blissfully happy. We were laughing about how we never eat at White Castle (we were a Chili’s family), and this was the first, and as it turned out the last time.

There was a part of me that knew it was a moment I had to cherish because it wouldn’t come back to find us again. I remember starting to cry in the backseat, quietly—hopelessly brushing against death for the first time.

This is the first time I’m writing about her. It’s taken me nearly nine years. I turn 27 in March, and I’m struck by how young I still am—how much life there is left to live—and how cruelly she was cut off from 28, 29, 30, and all the years that should have stretched endlessly forward. I have so many questions for her.

I wonder if she knew I read the sequel to Master of the Game—Mistress of the Game, written by Tilly Bagshawe, handpicked by Sydney Sheldon before his death to carry on the series. Did she know I kept both copies close, not because they’re great literature, but because they remind me of her?

I wonder what she would’ve looked like at 37. Would her hair have stayed long, or would she have chopped it short “just to see”? Would she have complained about her aging skin, or would she have pinched my cheeks and said, “I miss this skin,” laughing in the way she always did?

I wonder what kind of life she would have created for herself—if she had met someone or gone through with an arranged marriage, if her children would have looked like her, with her big, innocent smile and the kind of eyes that always seemed to hold a secret. I wonder if she would’ve liked The National if I played Lemonworld for her, or if she’d wrinkle her nose and say, “This is too sad—put on something with a beat.”

These are the things I hold onto—questions I will never have answers to, but somehow, they keep her with me, suspended in the what-ifs, the almosts, and the invisible moments that will always belong to us. In reality, all I have left of her are memories, each one neatly boxed up with a ‘last’: the last Bollywood movie we watched, the last Hindi song we sang to, the last delicious bit of gossip she shared about her friends, the last wedding we went together, the last trip to India, the last selfies we took.

From the age of 17, every three or four years, there was a rhythmic, almost cruel clock—a cycle of sudden loss I came to unconsciously anticipate.

In 2019, I said goodbye to my grandmother—the last living grandparent I had. I saw myself in her, not by choice, but by genetics. My family often commented that I was wearing the living essence of her features. I used to hate it when they’d point out our uncanny resemblance. What little girl wants to be physically compared to her grandmother? Now, I find it freeing—having a memory of what I’ll look like when I’m older, seeing her face in mine. My face in hers. An inheritance I never asked for, but was gifted anyway.

In 2022, I said goodbye to my mother’s childhood best friend, who was like a second mother to me. She was one of the first adults to encourage me to write, to see something in me that I hadn’t yet believed in for myself. I think about her every time I write—as a way to pay my respects. It’s my prayer, a form of devotion. When she passed, she took a piece of my mother’s soul with her, and a part of her still lives inside my mother. I see it when she talks about her—of their girlhood, adulthoods, choices, and the lives they built—with children, husbands, and their not-so-quiet dreams.

What a mess this is—to live a life after witnessing death. A balancing act in the margins of love, where grief lingers like an uninvited guest, standing in the corner of the room, sipping your wine, and making small talk.

But, if you can look past the mess, there’s a fractured beauty in it. You’ve heard me talk about the people I’ve lost, and what I’m saying now is just one version of how I hold them, in my mind, in this life of mine. How strange, how precious, that we get to hold onto our own version of those we love and lose. That we each carry our own story of them, a little blurry around the edges, or maybe too familiar, but never a perfect copy of anyone else’s.

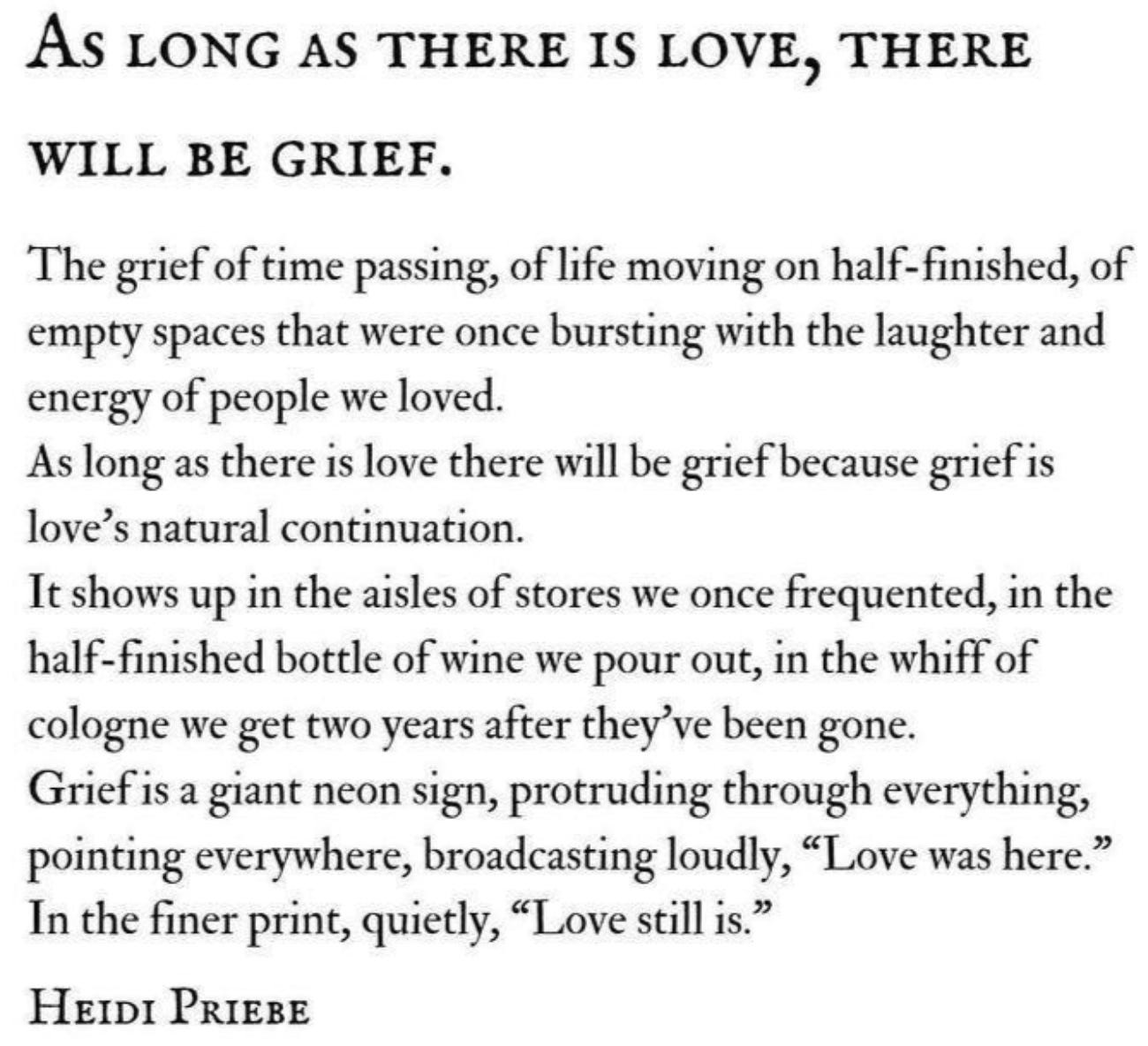

This may be why love and loss are so deeply entwined. When we think about love, we are prodded, probed—our eyes peeled back, forced to acknowledge that it’s everywhere, in everything.

Only when we experience death ourselves do we truly see it, too, in everything, all around us. It sneaks into the tiniest, unassuming symbols—like dog-eared pages of a book from the '80s, the curves of my smile lines, and stories tucked away on an old flash drive championed by someone who hadn’t even read them.

These traces are scattered through this miserable, golden world, and these symbols carry our capacity for something as ancient as love and as unscalable and elusive as death.

Field Notes

A curated collection of media recommendations aligned with this month’s theme:

Green Dreamer: “Sitting with the Wisdoms of Darkness, Death, and Decay” (podcast)

Freak Deaths by Aishwarya Mishra (short story)

PS Many thanks to PRATHIGNA for being such an incredible collaborator and friend. Your support made this first newsletter of the series truly special.

PPS If you haven’t already subscribed to The Guest House, what are you doing?!

well done ladies!

👏🏿👏🏿👏🏿 I love this series already!